Why Can’t I Get an Appointment?

It’s not because dermatology is undesirable as a profession. The average income is $381,000—more than even anesthesiologists and emergency medicine docs make—and in a 2013 study ranking the desirability of 18 specialties, students placed dermatology number one in terms of “best lifestyle.” What’s really amiss?

More people need derms than ever before.

People are living longer. Skin conditions that once bore terminal diagnoses are now treatable. Both good things, but they’ve also contributed to the crisis. Sixty-eight percent of dermatology patients are 40 years old or older. Approximately 87,110 cases of invasive melanoma will be diagnosed in 2017 alone, and more new cases of skin cancer are detected every year than cases of breast, prostate, lung, and colon cancers combined. All that leaves patients jockeying for space on an already congested schedule. “It requires more output from physicians to treat a patient over a longer period, and [this field wasn’t] built for that war from a labor standpoint,” says Travis Singleton, senior vice president of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

Hospital residency programs may keep derms away.

Aspiring derms face a hurdle: There aren’t enough training programs for them. In 2016, of the nearly 31,000 total residency spots available to graduating medical students in the U.S., only 420 were in dermatology (the top residency was internal medicine, which had 7,024 positions, followed by family medicine with 3,238 and pediatrics with 2,689).

Granted, all training programs at teaching hospitals are vulnerable because they depend largely on support from Medicare. “That funding stream for medical education has not seen meaningful growth in about two decades and, in fact, is often under threat,” says Jack Resneck, Jr., M.D., vice chair of the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) department of dermatology and a health policy expert.

But hospitals do get to choose how much of the Medicare money they allocate to each specialty. And it’s not in a hospital’s best interest to bring on tons of would-be derms for training, because “dermatologists don’t admit many patients for hospital stays and don’t order a lot of expensive tests like CT scans,” says Cincinnati dermatologist Brett Coldiron, M.D., who served as president of the AAD in 2014 and 2015. In other words, derm residents don’t generate much revenue for hospitals, Coldiron says. A 2014 report published by the National Academy of Sciences—a nonprofit organization that advises the government on scientific issues—concluded that the financial benefit to hospitals of having on-call dermatology residents is “minimal,” while surgery residents provide considerable revenue. (The American Hospital Association and the American Association of Medical Colleges declined to comment about the issue for this story.)

Some insurance companies don’t want to pay dermatologists.

The irony: Derms don’t rack up enough bills for hospitals, but they rack up too many for insurance networks, way more than GPs do. And insurers, of course, have to reimburse those bills. So some insurance companies decide that “if they block a little bit of access to care by limiting the number of dermatologists on their plans, they’ll collect premiums from people but not have to pay out doctors, and they will see less loss,” explains NYC dermatologist Deborah Sarnoff, M.D., president of the nonprofit Skin Cancer Foundation. This results in “narrow networks,” in which fewer patients get care.

Another tangle in the web? Physicians’ contracts “are being terminated without cause,” according to a 2014 UCSF study. Trade publications, like Dermatology Times, have noted that the most expensive dermatologists—the Mohs surgeons—are frequently dropped from insurance networks. (Mohs surgery is the standard and most effective way to remove basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas—the two most common types of skin cancer—and is increasingly used to treat melanoma.)

Resneck, too, is “concerned that some insurers may be removing those dermatologists from their networks who take care of the sickest or most vulnerable patients with the highest needs—and thus the highest costs—potentially driving those patients to select another insurer.” Coldiron, who has lobbied Congress about insurance issues, has seen this firsthand. “One insurance company went into a major city and said, ‘We’ll delist the 50 most expensive doctors,’” he says. “And the thing is, the delisted doctors generally perform more procedures. So they’ll delist the Mohs surgeons, or [those who see] the toughest psoriasis patients and prescribe expensive drugs.”

The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA)—the AAD’s sister organization that focuses on government affairs, health policy, and practice information—has been lobbying Congress since early 2014, when it says its members began receiving network termination notices. In a 2014 position statement, it made its stance clear: “The AADA is opposed to the practice in which health insurers reduce the size of their provider networks (i.e., engage in ‘network narrowing’) based on metrics related to cost.”

Do Skin Cancer-Screening Apps Really Work?

GO →

More than half of U.S. states have created laws aimed at improving networks. In 2015, California passed the most comprehensive of the bunch, a statute that increases state oversight of insurance networks’ adequacy. But it’s not a federal solution. “We need some sort of minimum regulatory standard for ensuring that patients have access to the providers they need,” says Kevin Lucia, project director at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

WH reached out to America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), the trade group that represents health insurance companies, for comment. Spokesperson Cathryn Donaldson denied the claim that insurers purposely remove dermatologists and pointed out that some derms themselves narrow the networks by choosing not to participate in plans. When asked why certain derms, including Mohs surgeons, have been dropped from plans seemingly without reason, she said, “Specific network configurations—including specialists in or out of network—will depend on the insurer, the plan, the region, and local market dynamics.”

The doctors in your insurance network may not even exist.

It’s smoke and mirrors: Some insurance companies continue to list the names of doctors who have retired, relocated, or died to make their networks look larger than they really are. According to the 2014 UCSF study, which investigated the accuracy of insurance plans’ dermatologist directories, only one out of four dermatologists listed as in-network in a popular nationwide health-care plan actually existed, accepted that plan, and offered appointments to new patients. Some had moved away or retired, some were duplicate listings, and others were totally mysterious—the researchers would call the phone number and a receptionist would answer and say they’d never heard of that doctor.

AHIP’s Donaldson acknowledges inaccurate physician directories are an issue, but says it’s unintentional and that her organization is taking steps to solve the problem, including by finding better ways to communicate with physicians to get updates. “Health plans depend on doctors to submit accurate and up-to-date information on details like provider and facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and languages spoken. And it is critical that doctors reach out to health plans when their information changes and that health plans make the updates in a timely manner,” she says. The UCSF study noted another reason insurance companies give for erroneous listings: “last-minute changes to federal health-care plans.”

Yet multiple dermatologists we spoke to said on the record that they believe these mistakes on insurance networks’ lists are purposeful. Coldiron called the companies’ tactics “insidious”; W. Patrick Davey, M.D., a clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, used the word “deceptive.” Resneck lamented that at the same time insurers are terminating derms from their networks, they’re also “keeping bloated, inaccurate rosters.” Sarnoff minced no words: “It’s all about saving money. [Insurance companies] use [doctors’] names to entice the patients to sign on and purchase the policy but don’t keep [doctor lists] up to date.” And though medical trade magazines have covered the issue, “it’s not publicized enough for people to understand what’s going on,” Sarnoff says.

Cosmetic patients get choice appointments.

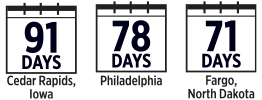

Patients with a possible melanoma wait more than three times as long for an appointment as those looking for younger-looking skin. So says a 2007 UCSF study in which researchers posing as patients called almost 900 dermatologists around the country. When they said they wanted wrinkle injections, they were given appointments within eight days—as opposed to an average of 26 days when they called complaining of a changing mole that fit the description of a melanoma.

And the appetite for cosmetic procedures has exploded. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, facial injections have jumped 7,000 percent (not a typo) between 1997 and 2016. More pointedly: During the past few years, as injection rates have increased by 10 percent, Americans are waiting a very similar 12 percent longer for derm appointments, according to doctor recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The issue isn’t the cosmetic treatments or injections themselves. It’s the old law of supply and demand—more people want cosmetic appointments, more people need medical appointments, and there just aren’t enough doctors to go around. Some experts point to money as a motive.

“Dermatologists may want to selectively improve access for these patients because of higher relative payments for cosmetic services,” the UCSF study authors write. As Bobby Buka, M.D., a New York City dermatologist, explains, “with cosmetic patients, dermatologists get paid up front by the patient directly, as opposed to medical visits, which involve insurance companies. The average time for a dermatologist to collect from insurance companies is 34 days, and oftentimes it can be a challenge to collect at all.”

There is a faction of derms who don’t think cosmetic appointments influence medical wait times at all. “I truly don’t believe that’s a reason,” says Sarnoff. “For the vast majority of derms doing cosmetic [work], it would be 10 percent or less of their practice. It’s important to note that [the UCSF research] is just one study and over a decade old.” But seven derms around the country—several of whom practice in or near deserts—told WHH that some dermatologists do prioritize cosmetic appointments over medical ones, and that most derms who offer cosmetic treatments now block off specific appointment slots for cosmetic versus medical patients. “Especially in slower economic times,” says Flint, Michigan, dermatologist Bishr Al Dabagh, M.D., “to stay competitive in cosmetics, a dermatologist must schedule a sooner appointment or risk losing that patient to a medi-spa or another practice.” (Al Dabagh himself does not offer cosmetic services.)

One dermatologist, who practices in the Northeast and asked to remain anonymous, noted that many derms are proactively trying to grow the cosmetic aspect of their practice even as medical appointments cannot be accommodated. One potential reason? “Many dermatologists can’t stay in business because they can’t manage all the government and health-insurance mandates. It’s become very cumbersome—the amount of things we have to report and document and follow,” says New York City dermatologist Doris Day, M.D. “Many dermatologists may need the aesthetic side to cover the medical side.” To wit, there’s almost a $100,000 difference in pay for doctors who do cosmetic procedures and those who don’t, “so it’s hard to blame them,” says Singleton of Merritt Hawkins.