This is not your typical Gym. There’s no thumping music, no barbells crashing to the floor. But these aren’t your typical gym rats filling the 4,000-square-foot Physical Activity Centre of Excellence, or PACE, at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. The average person using the weight and cardio machines on this freezing February morning is in his or her mid-70s. And everyone’s here for the same reason.

“Everybody gets stronger,” says Stuart Phillips, Ph.D., a professor of kinesiology at McMaster and one of the two men I’ve come here to see. At any given time, Phillips and his colleagues have dozens of the senior lifters involved in their research, which explores the complex relationship that protein and strength training have with human muscle, and the life-or-death consequences of putting (or not putting) that muscle to use.

Few people demonstrate this dynamic better than the second man I’m here to see. As Phillips points him out to me, John Nagy is knocking off a set of lateral raises on a rotary machine. At first glance, there’s nothing about Nagy, a compact man wearing steel-rimmed bifocals, that sets him apart from the 30 or so other people here. He could be your father, your grandfather, or any other active, disability-free 75-year-old.

Except he’s not. Nagy is 97. That’s almost double the average life expectancy for a man born in 1917. I want to know how the choices he’s made over the past century—his workouts, his diet, his attitude—helped him reach this improbable age.

A generation ago these might have been idle questions. Nobody worried about the strength or fitness of retirees. Sarcopenia, or age-related muscle loss and the catastrophic health problems associated with it, wasn’t even coined until 1988.

Today we know that muscle and strength are among the greatest assets we possess. It’s never too early to start building your portfolio, nor is it ever too late to add to it. After age 30, an untrained body tends to lose about 1 percent of its muscle mass each year. Strength declines even faster. Diminished muscle and degraded strength lead to less movement and lower fitness, which in turn lead to such chronic conditions as heart disease and diabetes. But while aging is inevitable, the worst aspects of it are not.

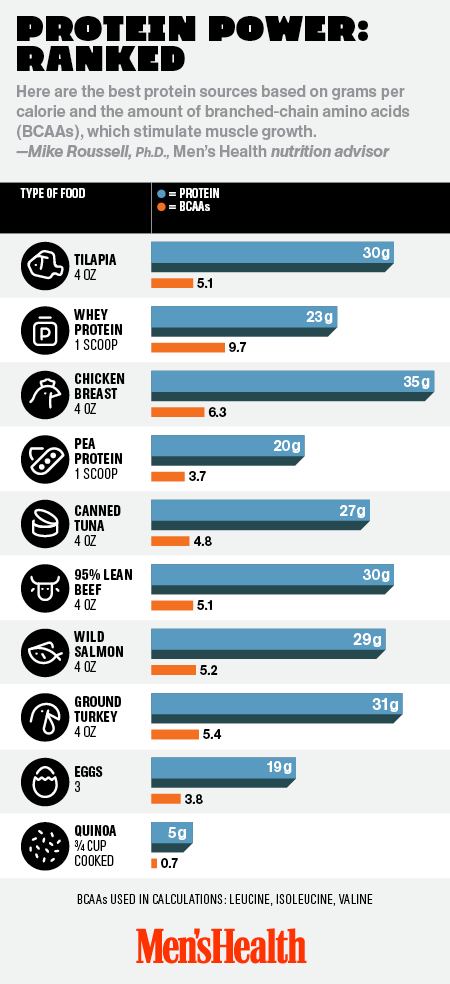

How Meat Makes You Amazing

Protein is vital to virtually every cell and process in your body. Donald Layman, Ph.D., a professor of food science and nutrition at the University of Illinois, explains the power it wields. —K. Aleisha Fetters

After his workout, Nagy greets me with a friendly smile and a firm handshake. It’s clear why he can carry himself like a man a quarter of a century younger: He started exercising every day as a kid and never stopped. He remembers 100 friends from his teenage years during the Depression, all with a similar love for sports. “We’d play baseball, football, hockey, lacrosse, skate, and swim in the bay,” he says. “Only three of us have lived into our late 90s. One guy skated all year. The other fellow swims every day. And I exercise every day. So I’m sold on exercise. I really and truly enjoy it.”

His 90-minute workout at PACE was actually his second of the day. Nagy keeps dumbbells, resistance bands, and “that new ball”—a Swiss ball—in his apartment, along with a treadmill and stationary bike. He starts his day with warmup movements in the shower, followed by floor and ball exercises for his core and back. When weather permits, he walks to McMaster—2 miles each way—and when it doesn’t, he makes up for it on his treadmill. Although Nagy has lost an inch of height (he’s now 5' 6"), his weight has barely budged: from 150 pounds in his 20s to 154 pounds now. He even did classic pushups until a recent shoulder injury forced him to modify them. (Now he does 3 sets of 8 reps from his knees.)

Nagy’s diet is a throwback too. He emphasizes nutrient-rich whole foods, with plenty of meat, fish, dairy, nuts, and legumes. “I eat everything,” he says. He goes on to describe a breakfast mix he makes from whole grains and dried fruit. His go-to dinner is protein-rich cabbage rolls stuffed with ground beef and rice, which he washes down with a glass of red wine.

To be sure, some of Nagy’s longevity is genetic. But genes don’t explain all. For example, a Finnish study looked at identical twins in their 30s who had different exercise habits. Despite having the exact same genes, the twins had already begun to see their health diverge in dramatic ways. Siblings who stayed active had less fat, better control of their blood sugar and insulin, and more gray matter in parts of the brain that regulate movement.

Other research tells similar stories. A study of adults in the U.K. found that those who had the worst composite scores on three fitness tests—grip strength, balance with their eyes closed, and functional ability (time needed to sit down and stand up from a chair)—at age 53 were almost four times as likely as the top performers to die over the next 13 years.

And if that doesn’t scare you, consider this: As part of a military draft exam, the Swedish government tested the strength (quadriceps, biceps, and grip) of more than a million teenage boys born between 1951 and 1976. Just over 26,000 of them died before their 55th birthday. But those who were strongest were up to 35 percent less likely to die before age 55 due to any cause.

The studies tested different things, but in the big picture of lifelong health, they all point in the same direction: Muscle, and the ability to use it to generate movement, is a matter of life and death.

It’s easy to wrap your head around the idea that high levels of cardiovascular fitness help you live longer. After all, if a strong heart can’t protect you from cardiovascular disease, what can? The same logic applies to obesity and diabetes: If you’re doing a lot of endurance exercise, you probably aren’t storing much fat and aren’t likely to have a problem controlling blood sugar.

The link between strength and longevity is less intuitive, because we tend to see cardio fitness and muscular fitness as two separate and unequal systems. “Everyone thinks of cardiorespiratory fitness as heart and lungs,” Phillips says. “But it’s the heart and lungs and brain talking to muscle and moving you around. If you’re fairly fit and fairly strong, you’re probably moving around a lot. And if you’re stronger, you’re probably making an effort to do things that preserve your strength.”

That last point is crucial. When research first showed that stronger people live longer and with less disability, the reason wasn’t immediately clear. Did strength make some people healthier? Or did illness make other people weaker?

John Nagy raises the bar.

The Cooper Clinic in Dallas tackled the causation problem with a long-term study that included men who lift. Men who were strongest on the bench press and leg press and reported training the most were found to be about 50 percent less likely to die in middle age than those who were weakest on these moves and reported training the least.

What’s clear is that losing muscle at any age is a metabolic disaster. In one recent study, Phillips had older people reduce the number of steps they took each day by 76 percent. In just two weeks, they lost almost 4 percent of their leg muscle while gaining fat. Even worse, they saw a rise in insulin resistance—a precursor of diabetes—and a decline in muscle-protein synthesis after eating.

The latter is a sign of anabolic resistance—your body’s struggle to store protein in muscles. Combine insulin resistance with anabolic resistance, and very, very bad things start to happen to a guy who isn’t exercising enough. “You begin to store fat in places where it should never be stored,” Phillips says. “You store it in your heart, your muscle, and your liver.”

There are, however, two ways to avoid that fate. The first is what we’ve been talking about: Get off your ass and lift. The second is a little more appetizing: Keep reading.

Food, to a scientist like Phillips, is energy. Each gram of protein, carbohydrate, or fat gives you a caloric load that your body can use for whatever it needs. Eat the exact right amount of food for your size and activity level and you achieve a nirvana-like state known as energy balance. Eat more than you need, though, and the result is less blissful.

Your body is happy to sock away excess fat or carbs. “Fat turning into fat—well, that’s easy,” Phillips says. “You just store it.” Your body is also good at converting excess carbs into fat, once the glycogen stores in your liver and muscles are fully stocked. (Additionally, you have a few grams—about a teaspoon’s worth—that circulate in your blood.)

Protein is different. Of the 20 amino acids that form protein molecules, only a few can be converted to fat, which means your body has a harder time pulling that off. That’s on top of two other well-known benefits: a high thermic effect (about a quarter of protein calories are burned during digestion) and increased satiety, so the more protein you eat, the less hungry you are for everything else. The opposite happens when you eat less protein: Your hunger increases and you can end up eating more total calories.

That last phenomenon is called protein leverage. The idea is that our bodies crave an optimal amount of protein, and once we’ve consumed it, our appetite shuts down. It usually takes a protein intake of 25 to 35 percent of total calories for the mechanism to kick in. That’s relatively high when you consider that a typical diet is about 15 percent protein.

When you consume more protein, you displace something else in your diet, Phillips says. You also need to eat protein more often. In a recent study, he tested two different meal patterns on a group of seniors. Those who ate four protein-rich meals throughout the day had better protein synthesis than those who ate most of their protein at dinner.

Phillips believes breaking up protein intake—eating 30 to 40 grams in each of three or four meals—is a crucial weapon against anabolic resistance. It works best when combined with strength training. For convenience, the men had protein shakes for breakfast and as a late-night snack. His study showed that their muscles were still more receptive to protein 48 hours after lifting.

Animal foods are the most conducive to muscle growth. “Most of the protein in our bodies is meat,” says obesity researcher Stephan Guyenet, Ph.D. “So it’s not a surprise that protein from meat has a favorable distribution of amino acids.” In fact, all animal proteins, including meat, dairy, and eggs, are complete: They contain all nine essential amino acids, the ones your body can’t synthesize. (If you’re a vegetarian, focus on complete plant proteins, such as quinoa, buckwheat, and amaranth, as well as a variety of other sources, such as beans, lentils, wheat, nuts, and seeds.)

When meat on the menu becomes meat on your bones, it serves an underrated purpose. “Muscle is an amino acid reserve,” says Andy Galpin, Ph.D., C.S.C.S., of Cal State Fullerton, who studies muscle on the cellular level. “You’re literally harboring excess amino acids in your muscles.” You can use them on a daily basis for a long list of tasks, from repairing tissues to producing hormones and enzymes. This becomes critical to maintaining whole-body and muscle health in the event of disease and also as you age.

Still, the biggest benefits you’ll gain from muscle tissue come when you actually use it. That’s when you generate hormones that not only make you stronger but also help you become smarter.

Here’s the bad news: “Your brain starts to age in your late 30s and slowly declines from there,” says kinesiologist Jennifer Heisz, Ph.D., whose research at McMaster looks at the links between physical and mental health. The good news? Your muscles may be the best tools you have to slow the decline.

Of the seven factors that accelerate the loss of your marbles, exercise is known to improve five of them: physical inactivity, depression, obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure. (The other two are smoking and “cognitive inactivity.”)

But using your muscles also improves your brain in more direct ways. For starters, exercise triggers an increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, which helps support the growth of new brain cells. “The hippocampus, where many BDNF receptors are, is a critical center for memory and learning,” Heisz says. It’s also a brain region devastated by Alzheimer’s.

Then there’s stress. Normally we view stress as bad for the body and mind because, like obesity and diabetes, it’s linked to chronic inflammation. Other than blunt trauma, there aren’t many things worse for your brain than inflammation. But the temporary kind of stress response to exercise comes from deep in our evolutionary history and has a very different effect.

Imagine you’re a cave-bro out on a hunt. As you move, your brain is on high alert. If something unexpected happens, good or bad, you get a surge of adrenaline, the fight-or-flight hormone. It helps your muscles receive energy and also helps your brain encode the information for future reference. When the adrenaline dissipates, another stress hormone, cortisol, rises. Its job is to consolidate the memories while also preventing new memories from intruding on it.

The chronic elevation of stress hormones has the opposite effect. They handicap the parts of your brain that form new memories, accelerating your brain’s aging. That’s why Phillips sees lifelong health as a three-legged stool: “There’s physical activity, nutrition, and stress.” For the stool to do its job, the three legs have to be equally solid.

With physical activity, everything has some benefit. For you, right now, the biggest benefits will probably come from increasing your overall work capacity and fatigue resistance.

Nutrition is a lifelong balancing act. Most of us will move less and eat less as we age; yet we typically add a little weight. That means we’re losing muscle while replacing it with an equal amount of fat—and then some. A 5-pound weight gain in midlife might actually represent a 10-pound fat increase combined with a 5-pound muscle loss. That’s almost guaranteed to worsen your health.

You can minimize the damage with a diet that’s higher in protein, as mentioned. But the best strategy by far is to put your muscles to work. “If you don’t exercise, the only way your body has to deal with excess energy is to store it,” Phillips says. When you do exercise, you not only store less energy but also pull some of the energy you already have out of fat cells and into circulation. Plus, with strength training you break down muscle tissue with the goal of replacing it with dietary protein. Even if you don’t lose any weight, Phillips says, you’re at least moving it around. “The storage starts to go down, and you lower your risk for metabolic diseases.”

That leaves stress, the third leg of the stool. For that, let’s return to someone who knows a few things about managing it.

Nagy remembers the most stressful time of his life. The year of his divorce he retired, sold his house, and became an expat. With three suitcases he moved to Hungary, Trinidad, and then Florida before coming home. “When you’re young, you can do those things,” he says. He was 65 at the time.

He kept his equilibrium the way he always has: by enjoying what he does and the people he meets while doing it. He still remembers the names of his coworkers at a cotton mill when he was 15. He liked his job at a fertilizer plant before WWII, and his later teaching job, and his 30 years as a probation officer. “It’s primarily because of the people you meet.”

It’s no surprise that the affection for the people he’s around most carries over to his workout buddies at McMaster. “One of the reasons I come here is socializing,” he says. “There’s a damn good group.”

Something all those senior lifters have in common is that they aren’t worried about their life span, Phillips says. “When you talk to people, they don’t want longevity. They’re not looking for a drug that helps them live to 103 if the last 10 years are in dependent care. What they want is a good ‘health span.’”

That’s the good life—for them, for you, for anybody. Muscle can’t guarantee you happiness, but if nothing else, it keeps you on your feet as you search for it. “Come on,” Nagy says. “What more do you want?”

Give Your Life a Lift

Ace these three strength tests, and stay out of life’s express- checkout lane.

1. Know the Minimum Strength You Need for Longer Life

At the Cooper Clinic, researchers found that the weakest men on two moves—the bench press and leg press—had the highest risk of premature death. They lifted an average of 70 percent of their body weight on the bench press machine, and 1.4 times their weight on the leg press. The former is the equivalent of a pushup with your feet on a 12" box; the latter is equal to a squat holding just over half your body weight. Risk fell among guys who could bench 90 percent or more of their weight and leg-press at least 1.7 times their weight. The equivalent: Do 10 pushups with feet elevated, and squat two-thirds of your body weight.

2. Master This Movement to Preserve Your Independence

When oldsters go to assisted living, it’s often because they can no longer use the bathroom solo, says Andy Galpin, Ph.D., C.S.C.S., a muscle researcher at Cal State Fullerton. They need lower-body strength to get up and down, and balance and coordination to wipe. To stave off that fate and to test and hone your lower-body fitness, do split squats. Stand with one foot about 36 inches in front of the other, your hands behind your head. Lower yourself slowly until your back knee touches the floor. Pause and return to the start. If you can do 5 good reps with each leg forward, you’re ahead of the game.

Intensify Your Regular Workouts and Extend Your Longevity

Exercise science uses a unit called MET (“metabolic equivalent of task”) to gauge intensity. Sitting perfectly still is 1 MET; a cross-country skier hit 26, among the highest recorded. For each 1-MET increase in work capacity, your risk of dying of anything within a given period drops 12 percent. Here are few benchmarks.

- 5: Walking at 4 mph on a flat surface

- 6: Serious strength training

- 7: Using the rowing machine

- 8: Insanity-type metabolic workout

- 9: Tree trimming or heavy shoveling

- 10: Running 10-minute miles

- 11: Rock climbing

- 12: Boxing

Photographs by Finn O’Hara/Getty Images Assignment for Men’s Health